Plymouth’s $2.9 million beach nourishment project uses sand mined through the destruction of Carver’s forests and leveling of hills

Above: Site of the 120-acre A.D. Makepeace sand mine in Carver where forests have been clear-cut and valuable silica sand is extracted from beneath the hills. The sand mined from this area was transported to Plymouth Beach in 2023. As of May 2024, this remains an active sand mining site. Prior to strip mining, this area was an intact Pine Barrens forest classified under BioMap3 as “Interior Forest,” designated as high priority for protection. The mine is adjacent to two ponds identified by the Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program as Priority Habitats 512 and 514.

-

Sand erodes, blows out to sea

-

Taxpayer funded project OK’d in backroom deal between Carver Earth Removal Committee and sand mining giant AD Makepeace Co.

-

Beach nourishment is a $7 billion industry — Makepeace cashes in

-

Does clearing our forests and leveling hills to replenish the beach make sense?

The $2.9 Million Plymouth Beach Nourishment Project of 2023

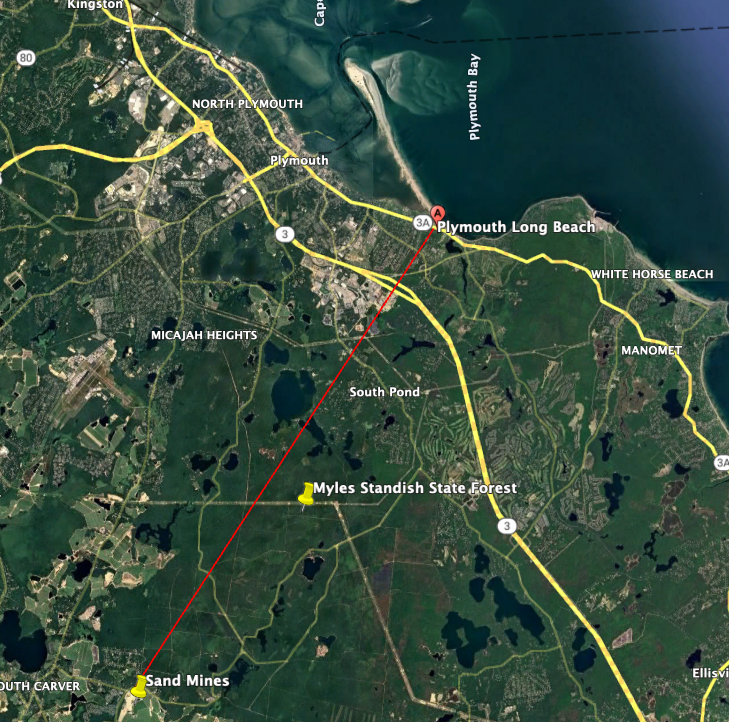

In 2023, the Town of Plymouth, with $2.9 in taxpayer funding from the state contracted with Dig It Construction to install a “beach nourishment” project on Plymouth Long Beach. Read the Town’s letter to Dig It Construction here. The Plymouth Letter to Dig It is here.

Dig It planned to get the sand from AD Makepeace’s Read Custom Soils in Carver, about 9 miles from the Beach. Someone claimed that Makepeace’s “Load Restrictions” for sand hauling (the number of truckloads of sand it can haul off in a day) limited the ability to bring enough sand to Plymouth. So Plymouth and Carver got together with Makepeace to pursue a “waiver” from the Carver Earth Removal Committee. This was a ruse because Makepeace already had numerous earth removal permits allowing at least 150 trucks loads a day to leave Carver with sand. Learn more about Makepeace’s “earth removal “permits here.

Below: Makepeace mined the sand from pristine forests in Carver. Dig It Construction and other contractors trucked the sand about 9 miles from the mines to Plymouth Beach.

Makepeace’s Backroom Deal: Seeking Carver Earth Removal Bylaw Waiver to Increase Sand Sales

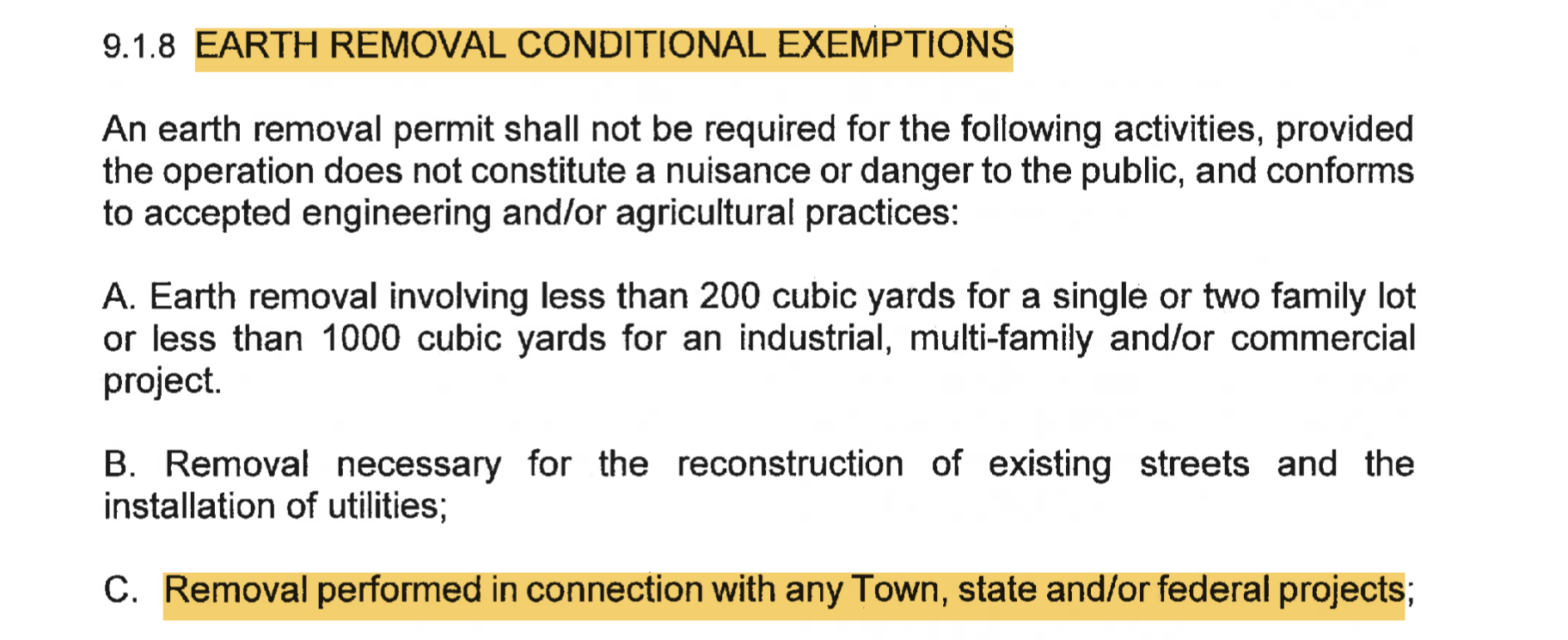

Despite holding at least four sand mining permits from Carver and transporting hundreds of truckloads of sand daily, Makepeace claimed it did not have enough for the Plymouth project. The manager of Read Custom Soils requested an “emergency waiver” from the Carver Earth Removal Committee to exempt Makepeace from the Town’s Earth Removal Bylaw. The Makepeace Letter addressed to the ERC can be found here.

The ERC granted the waiver as expected. The ERC Letter dated February 14, 2023, confirming the waiver for Makepeace, is available here.

The ERC letter verifies that the sand originated from Makepeace’s mines at Read Custom Soils on Federal Road in Carver. This allowed Makepeace to haul 50 truckloads per day, totaling 35,600 cubic yards, to Plymouth. With fees set at 25 cents per cubic yard for earth removal, A.D. Makepeace should have paid at least $8,900. However, they were exempt from paying these fees due to the emergency waiver.

Below is the Bylaw Makepeace and the ERC exploited to be able to take more sand from Carver to sell.

When resident investigators tried to find out the truth behind the back room deal, Carver’s lawyers refused to release all of the public records, claiming “Attorney Client Privilege” with the ERC. This is wrong. The ERC is a public entity — accountable to the public. Read the lawyer’s letter here.

See the Carver Earth Removal Bylaw here.

Who is AD Makepeace Co. and Read Custom Soils?

A.D. Makepeace and its subsidiary, Read Custom Soils, operate the largest aggregate sand and gravel mining operation east of the Mississippi. A.D. Makepeace also holds the distinction of being the largest landowner in Massachusetts. Their operations involve strip mining their land for sand and gravel, which is then marketed and sold through Read Custom Soils.

Learn more about AD Makepeace’s sand mining in the Sand Wars Report here.

Below: Another AD Makepeace sand mining location in Carver. This is the same day that the sand was being hauled to Plymouth Beach. March 23, 2023.

Conflicts of interest?

One of the companies that transported sand for Makepeace to Plymouth beach was Oiva Hannula Co., a cranberry and trucking company based in Carver, MA. In 2023, Scott Hannula, president of Oiva Hannula & Sons, Inc., was appointed as chair of the Carver Earth Removal Committee (ERC). The ERC is tasked with enforcing the Earth Removal Bylaw to promote public health, safety, and welfare. Scott Hannula benefits financially when the ERC grants permits to sand mining companies like AD Makepeace Co., as his company is hired to transport sand for these permitted operations.

Below: Hannula’s truck delivering sand to Plymouth Beach for AD Makepeace Co. Photo: 3/23/2023 Plymouth MA, Long Beach project.

Understanding Beach Nourishment: Is It Worthwhile?

A beach nourishment project is a coastal management strategy designed to restore eroded beaches or improve existing ones by adding sand or other sediments. Typically, this involves dredging or mining sand from alternate sources and depositing it onto the beach to expand its width or raise its elevation. However, sand is a finite resource. Is it sensible to strip mine land to place sand on a beach where it will inevitably erode or be carried away by wind and waves?

Learn more here.

The Hidden Costs of Beach Nourishment Projects

This isn’t the first project of its kind, and it’s likely not the last. Beach nourishment efforts often need to be repeated as sand inevitably blows away or returns to the ocean. While it provides a short-term fix for ongoing coastal erosion, exacerbated by more frequent and severe storms, research in Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science (Parkinson, Ogurcak 2021) indicates that beach nourishment isn’t a sustainable solution for mitigating climate change impacts on coastal communities.

These repeated projects come with costs and ecological disruptions, potentially impacting local habitats and wildlife. Despite being touted as a nature-based solution, beach nourishment has serious consequences. The extraction, transportation, and deposition of sand can disrupt ecosystems and marine life, disturbing the delicate balance of shorelines. Negative impacts include the burial of biota, loss of habitats in nearshore sandbars, and disturbance of bird and other animal nesting areas. Moreover, some species, like sand-dwelling invertebrates, are sensitive to changes in sediment types. The placement of large quantities of sand can smother these benthic or invertebrate communities, which serve as vital food sources for many seabirds and fish species.

At What Point Do We Stop Mining Sand to Dump on Beaches Where It Erodes Out to Sea?

Plymouth’s Long Beach, a narrow, elongated barrier beach stretching about three miles northwest from Plymouth’s mainland, is regularly fortified against storm surges and erosion through taxpayer-funded “beach nourishment” projects conducted by the Town and state.

It is estimated that “More than $7 billion has been spent in the United States in recent decades on artificially rebuilding hundreds of miles of beach nationwide.” (Beiser, 2018).

To source sand and sediment, we must mine for it somewhere else, removing earth and leveling hills or mining below the surface of the earth. Globally and in Southeastern Massachusetts sand mining is a major business. It destroys the environment and threatens our drinking water. By removing layers of sand, soil, and sediment, we are removing parts of our natural water filtration system. Find our more here.

Most sand mining is illegal and unregulated. As we are attempting to correct the natural process of shifting sands and inevitable patterns of erosion on the beach, we are mining for sand in nearby locations to supplement.

Should we keep altering and reinforcing the beach ourselves, or should we let this natural barrier beach change naturally with the waves, tides, and storms?

Below: Sand blowing out to sea at Plymouth Beach. This is sand mined by Makepeace in Carver for the beach project. 3/23/2023. Residents reported sand blowing out to sea regularly during the project.

Other Coastal Towns: Duxbury, Provincetown, and Salisbury MA

Duxbury has active beach nourishment projects. In 2023-2024, the town transported 168,000 cubic yards of sand from Duxbury Construction to nourish Duxbury Beach, supplemented by an additional 120,000 tons from Duxbury Beach Park, totaling about $2 million worth of sand. A recent article acknowledges that much of this sand will erode away relatively quickly. At a recent public forum, there was discussion about sourcing sand and gravel from various local pits.

In Provincetown, ongoing beach nourishment projects have faced opposition from the shellfish industry, which argues that the sand projects are burying their oyster grants and smothering native grasses. The town is now exploring alternative methods. Read more about it here.

In 2024, coastal homeowners in Salisbury spent $565,000 to truck in 15,000 tons of sand to bolster dunes against erosion. Unfortunately, most of it washed out to sea within days. Despite these setbacks, residents are seeking state funding to reinforce Salisbury Beach’s defenses. Read more here. Republican state Senator Bruce Tarr plans to seek $1.5 million in state funding to help strengthen the dunes at Salisbury Beach.

Learn more:

Sand Wars Film: Short Version 5 min. Long Version 10 min.

Website: www.sandwarssoutheasternma.org

United Nations Environment Program here.

Alternatives to sand mining: here and here. We must acknowledge the intricate interplay between human activities and the health of our ecosystems. We can work toward more sustainable solutions to preserve our beaches and protect our natural environments for future generations.